Coordinated Care Organizations now operate in one of the most demanding environments in US healthcare. The original promise of the CCO model was integration: aligning physical health, behavioral health, oral health, and community services under a single accountability structure. That promise has not changed. What has changed is the pressure under which it must now perform.

Value-based contracts are no longer experimental. Downside risk is becoming standard. Medicaid programs are tightening performance expectations while expanding reporting requirements. Behavioral health integration has shifted from a policy goal to a measurable obligation. In this environment, CCOs are being judged less on intent and more on execution.

Many organizations have strong clinical strategies on paper. They have policies for integration, care coordination, and population health management. Yet day to day operations often tell a different story. Data arrives late. Referrals stall. Care teams work hard but without a shared, real-time view of what is actually happening across the network. Leadership reviews reports that describe the past while frontline teams struggle to manage the present.

This gap between design and reality is where the CCO model either matures or breaks down. Technology is no longer a supporting layer added for efficiency. It has become the operating foundation that determines whether coordination is reliable or fragile, proactive or reactive, scalable or dependent on individual effort.

To understand how technology truly strengthens the CCO model, we need to look beyond tools and dashboards. The real question is how unified data, shared operational visibility, and execution-focused workflows turn coordination from a structural ambition into something that works consistently at scale.

Why most CCOs still underperform despite strong clinical intent?

If the pressure on CCOs is higher than ever, the obvious question is why so many still struggle to perform consistently. The answer is rarely a lack of clinical expertise or commitment. Most CCOs are filled with capable teams who understand the goals of integration and value-based care. The breakdown happens in how those goals are translated into daily operations.

At a high level, the CCO model is designed around global budgets, shared accountability, and coordinated delivery across multiple domains of care. On the ground, however, many organizations are still operating with systems and habits shaped by fee-for-service logic. Data flows slowly. Incentives remain uneven across providers. And coordination depends heavily on manual workarounds that were never meant to scale.

One of the most common friction points is the gap between design and operations. Leadership may assume that care coordination is happening because programs exist or reports are generated. In reality, frontline teams are often piecing together patient context from multiple systems, relying on delayed claims data, or manually tracking follow-ups in spreadsheets. Without real-time operational visibility, population health management becomes reactive by default.

Coordination also breaks down at organizational boundaries. Hospitals, clinics, behavioral health providers, and subcontractors often operate on different timelines and systems. Even when data sharing agreements exist, competing priorities and inconsistent compliance mean critical information does not always move when it should. Transitions of care, referrals, and post-discharge follow-ups are especially vulnerable, not because no one cares, but because ownership becomes diffuse the moment a patient crosses systems.

This disconnect is most visible between leadership expectations and frontline reality. Executives are held accountable for value-based performance, quality scores, and cost containment. Frontline teams, meanwhile, face workforce shortages, tool fatigue, and shifting regulatory guidance that arrives too late to shape care delivery. The result is an accountability gap where leaders expect uniform outcomes, but teams lack the operational infrastructure to intervene at the right moment.

Until this gap is addressed, even well-designed CCO strategies will continue to underperform. And that leads to the deeper issue that sits underneath nearly every operational challenge CCOs face: fragmented data that creates the illusion of control without the substance of visibility.

The hidden cost of fragmented data in CCO operations

Once the gap between strategy and execution becomes visible, fragmented data almost always sits at the center of it. Most CCOs do not suffer from a lack of data. They suffer from data that is delayed, incomplete, or disconnected across systems that were never designed to work as one.

From a leadership perspective, this fragmentation is dangerous because it creates a false sense of visibility. Dashboards exist. Reports are generated. Metrics are reviewed in committees. Yet much of that information reflects what happened weeks ago, filtered through claims cycles and manual reconciliation. What looks like control is often hindsight.

For frontline teams, the cost shows up immediately. Care coordinators routinely spend a significant share of their day chasing information instead of acting on it. Behavioral health notes live outside the primary EHR. Referral status has to be confirmed by phone or email. Social needs data arrives late or not at all. When coordinators are forced to reconstruct a patient’s story across multiple systems, coordination slows and burnout accelerates. Industry estimates routinely show care managers spending 20 to 30 percent of their time on manual data gathering rather than direct patient engagement.

Fragmented data also distorts decision-making. Leaders may believe emergency department utilization is stable because claims-based reports say so, only to discover a surge weeks later. High-risk members remain invisible because behavioral health encounters or social risk indicators are not integrated into risk models in real time. The organization reacts after costs have already escalated, rather than intervening when outcomes were still steerable.

Resource allocation suffers as a result. Programs are often funded based on where data looks clean and complete, not where risk is actually emerging. Low-acuity populations receive attention because their metrics are easy to track, while complex behavioral health cases fall through reporting gaps. Over time, this mismatch erodes both quality performance and financial predictability under global budgets.

What makes this especially challenging is that none of these failures feel dramatic in isolation. They accumulate quietly. Each delayed update, missed referral, or duplicated test adds friction until coordination becomes reactive by default. At that point, the CCO model is no longer operating as an integrated system, even if the structure still exists on paper.

Addressing this problem requires more than better reporting or more frequent data feeds. It requires treating data unification as a core operating strategy, not an IT cleanup effort. And that shift fundamentally changes how coordination is managed across the organization.

Why data unification must be an operating strategy, not an IT project?

When CCOs talk about fixing data fragmentation, the conversation often drifts toward interfaces, integrations, or reporting upgrades. Those efforts matter, but on their own they rarely change outcomes. The reason is simple. Fragmentation is not just a technical problem. It is an operational one.

Data unification becomes transformative only when it is treated as part of how the organization runs day to day. Instead of asking how systems connect, high-performing CCOs ask how information moves with the patient, the referral, and the decision. The goal shifts from assembling reports to enabling action while there is still time to intervene.

In a unified operating model, data is organized around the member journey rather than departmental ownership. Clinical encounters, behavioral health notes, referral status, care management activity, and community inputs all update a shared, real-time view. This does not replace existing EHRs or payer systems. It sits above them, translating raw data into operational signals teams can actually use.

The difference becomes visible quickly. Care coordinators no longer wait for claims to confirm that a follow-up was missed. Referral status updates in real time, making delays obvious before they turn into care gaps. Behavioral health engagement is visible alongside physical health utilization, allowing risk stratification to reflect the full picture instead of partial snapshots.

For leadership, this shift changes how performance is managed. Instead of reviewing lagging indicators after the fact, executives can see where workflows are starting to drift while there is still room to correct course. A rise in overdue behavioral health follow-ups or delayed post-discharge outreach becomes an early warning, not a retrospective explanation.

Most importantly, unification reduces the hidden tax on frontline teams. When data is automatically reconciled across systems, coordinators spend less time searching and more time acting. Workflows become clearer because everyone is operating from the same source of truth. Accountability sharpens because ownership is visible at each step, not buried in disconnected systems.

This is the point where data stops being something the organization reports on and starts being something it runs on. And once that foundation is in place, it becomes easier to see where care gaps actually originate inside CCO operations.

Where care gaps actually originate inside CCOs?

The first breakdown happens at transitions of care. When a member is discharged from an inpatient setting, responsibility often fragments immediately. One team records the discharge as complete, another waits for notification, and a third assumes follow-up is already underway. Even short delays, such as a 24 to 48 hour lag in notification, can be enough for behavioral health follow-ups or medication reconciliation to slip. On paper, the handoff occurred. Operationally, ownership dissolved.

Referrals create a second, more persistent gap. In many CCOs, referrals are sent but not truly tracked. Primary care providers may initiate a behavioral health referral, yet there is no closed-loop confirmation that the appointment was scheduled, attended, or completed. Studies consistently show that roughly 30 to 40 percent of behavioral health referrals fail to close when real-time tracking is absent. By the time claims data reveals the miss, the opportunity for early intervention has passed.

Asynchronous timelines compound both problems. Claims arrive after care is delivered. Behavioral health documentation lags behind encounters. Community-based services update information manually, if at all. Care coordinators are forced to work with yesterday’s picture while today’s risk is still forming. When emerging crises are invisible in real time, coordination becomes reactive by design.

What makes these gaps especially dangerous is that accountability is diffused rather than absent. Everyone plays a role, but no one owns the outcome end to end. Metrics reward task completion instead of continuity, and success is measured at individual touchpoints rather than across the full care journey.

Until these structural blind spots are addressed, adding more staff or more reports will not close gaps reliably. What does close them is shared operational visibility that turns transitions, referrals, and follow-ups into owned, trackable work across the entire network.

Closing care gaps through shared operational visibility

Once care gaps are understood as operational failures rather than clinical ones, the solution becomes clearer. Gaps close not when more policies are written, but when everyone involved in a member’s care is working from the same, real-time picture of progress and responsibility.

Shared operational visibility changes coordination from a series of disconnected handoffs into a continuous flow. When inpatient teams, outpatient providers, behavioral health clinicians, and care coordinators all see the same status at the same time, delays stop hiding in the spaces between systems. Everyone knows what has happened, what is pending, and who owns the next step.

This shift is especially powerful during high-risk transitions. A post-discharge behavioral health follow-up no longer lives in a discharge summary that may or may not be read. It becomes a visible, time-bound task with clear ownership. If the follow-up is delayed, the delay is obvious immediately, not weeks later in a report. Accountability moves from assumed to explicit.

Operational visibility also turns passive alerts into active work. Instead of sending reminders that blend into inbox noise, effective coordination systems assign tasks, track completion, and escalate when timelines slip. A referral marked as pending is not just a status. It is a responsibility with a clock attached. This is where coordination stops being conceptual and becomes measurable.

For frontline teams, this clarity reduces cognitive load. Care coordinators and case managers do not need to remember which referrals to chase or which follow-ups might be overdue. The system surfaces what matters most right now, based on real conditions rather than static rules. That allows teams to focus their effort where delays would cause the most harm.

For leadership, shared visibility closes the gap between expectation and execution. Instead of relying on retrospective summaries, leaders can see coordination effectiveness as it unfolds. Patterns such as rising overdue follow-ups in a region or stalled referrals within a specific provider network become visible early enough to intervene.

At this stage, coordination starts to feel reliable rather than heroic. But visibility alone is not enough. To scale across growing populations and networks, coordination must also move beyond manual tracking and individual effort. That is where many CCOs hit their next ceiling.

Why manual care coordination fails at scale

Many CCOs function today because dedicated care managers compensate for fragmented systems through sheer effort. Spreadsheets, reminder lists, phone calls, and email threads hold coordination together. For a time, this approach works. But it works by stretching people, not by strengthening the system.

As populations grow and networks expand, the volume of transitions, referrals, and follow-ups increases faster than any individual’s capacity to track them. Manual systems have a hard ceiling. Even the most organized care manager cannot reliably monitor hundreds of concurrent tasks across physical health, behavioral health, and community services without real-time support.

This dependence on individual vigilance creates fragility. When coordination succeeds, it is often because a small number of high-performing staff members absorb the complexity. When those individuals burn out or leave, continuity degrades quickly. The organization does not fail all at once. It begins to miss small things, then larger ones, until gaps reappear as avoidable emergency visits, missed follow-ups, or quality shortfalls.

There is also a human limitation that no amount of training can overcome. Manual tracking forces care teams to spend valuable time searching for updates rather than engaging with members. Decision fatigue grows as task lists expand, and prioritization becomes reactive. The system ends up rewarding urgency and persistence rather than risk and impact.

It is tempting to believe that better care managers or more staff will solve this problem. In reality, strong teams already handle as much as they can. What they cannot do is scale reliably without support. Sustainable coordination requires workflows that extend human capability rather than exhausting it.

This is the point where technology must do more than store information. It must actively support coordination by organizing work, prioritizing risk, and synchronizing action across teams. When that happens, care coordination stops depending on heroics and starts functioning as a system.

Technology-enabled coordination workflows that actually work

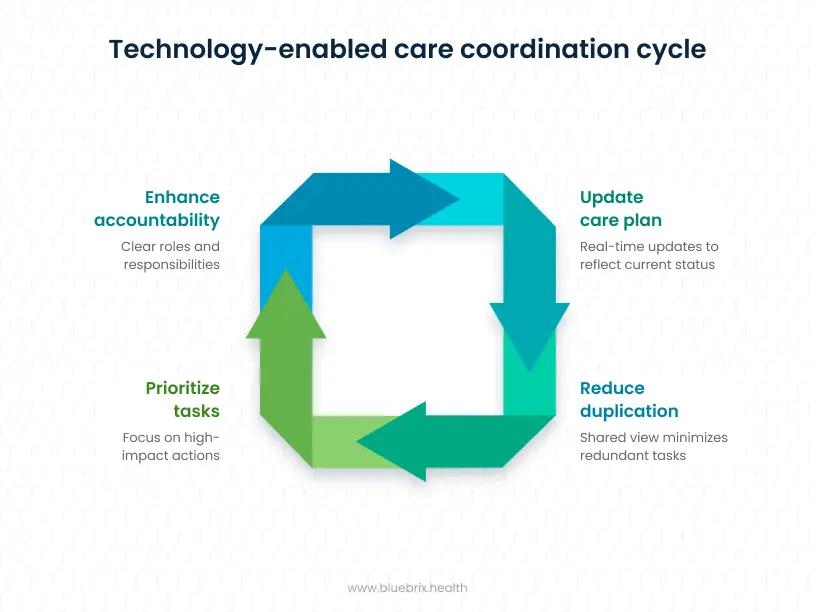

When care coordination is designed to scale, technology shifts from being a passive record system to an active coordination layer. The goal is not to replace human judgment, but to organize information and work in a way that makes good decisions easier and delays harder to miss.

Effective coordination workflows start with shared care plans that reflect reality, not just compliance requirements. Instead of static documents updated after the fact, the care plan becomes a living operational view. Clinical encounters, behavioral health visits, referral activity, and care management notes all update the same plan in real time. Every team sees what has been completed, what is due, and what is overdue without having to ask or search.

This shared view reduces duplication immediately. When one team completes an intervention, others see it and adjust accordingly. Members experience fewer repetitive calls and more coherent outreach. For staff, time previously spent confirming status is redirected toward engagement and problem solving.

Prioritization also changes. Rather than working from long task lists or responding to the loudest alert, modern coordination platforms continuously assess risk across multiple signals. Missed visits, utilization spikes, behavioral health engagement, and social risk factors are evaluated together. Work is then ordered based on potential impact, not memory or urgency. Care managers start their day knowing which actions matter most right now.

Coordination across teams becomes clearer as well. Role-based views show who last engaged the member, what action occurred, and what is next. Built-in safeguards prevent two teams from performing the same outreach or leaving a task unowned. Accountability is embedded in the workflow, not dependent on follow-up meetings or email threads.

For leadership, these workflows provide something traditional systems cannot. They offer a direct line of sight from daily activity to coordination effectiveness. Instead of asking whether programs exist, leaders can see whether work is actually moving, where it is slowing, and how teams are responding in real time.

At this stage, coordination is no longer fragile. But visibility and workflow alone are not enough. To guide an organization under value-based contracts, leaders also need analytics that support decisions, not just reporting.

Why CCOs need analytics, not more reports?

As care coordination becomes more reliable at the workflow level, the next question for CCO leadership is how to steer the organization proactively rather than react to results after the fact. This is where many analytics environments fall short. They explain what happened, but they do not help leaders decide what to do next.

Traditional CCO reporting is built for accountability. It summarizes emergency department utilization, screening rates, follow-up completion, and quality scores for audits and external stakeholders. These views are necessary, but they are retrospective by design. By the time a trend is visible, the underlying issue has often been present for weeks.

Decision-support analytics work differently. Instead of waiting for lagging indicators, they continuously interpret live operational data. Patterns such as rising overdue behavioral health follow-ups, slowing referral closures in a specific region, or increasing utilization among a high-risk cohort surface early, while intervention is still possible.

This shift changes how leadership operates. Rather than asking teams to explain why performance declined, leaders can redirect resources before performance slips. Staffing can be adjusted, outreach intensified, or workflows corrected in response to early signals rather than quarterly summaries. Analytics move from passive observation to active guidance.

Trust is critical here. Leaders act faster when they believe the data reflects reality. When analytics are fed directly from real-time coordination workflows rather than delayed claims or manually curated reports, confidence improves. Decisions feel less like guesses and more like informed adjustments.

In mature environments, analytics become part of daily management, not a separate reporting function. Leaders see where coordination is starting to drift, trust what they see, and act decisively. At that point, analytics stop documenting performance and start shaping it.

Once decision support reaches this level, the final test for any CCO emerges. Do these operational gains translate into measurable success under value-based contracts?

Aligning technology with value-based accountability

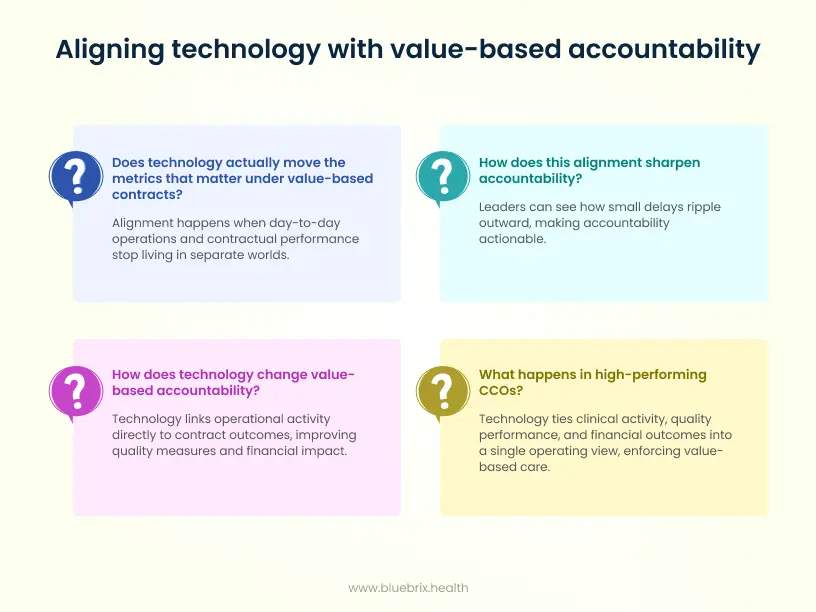

Once coordination workflows are reliable and analytics guide real decisions, the final question for CCO leadership is whether these capabilities actually move the metrics that matter under value-based contracts. Alignment happens when day to day operations and contractual performance stop living in separate worlds.

In many CCOs, value-based accountability is still managed backward. Quality teams track measures. Finance teams monitor cost trends. Operations teams focus on throughput. Each function does its job, but the connections between them remain loose. The result is a familiar frustration where everyone works hard, yet performance under downside risk still feels unpredictable.

Technology changes this when it links operational activity directly to contract outcomes. When referrals close on time, follow-ups happen within required windows, and care plans stay current, quality measures improve as a natural result of better execution. There is no separate program to chase metrics. The work itself produces the score.

The financial impact follows the same pattern. Unified platforms continuously monitor utilization trends, risk trajectories, and engagement signals across the population. When rising risk is detected early, teams intervene before avoidable emergency visits or hospitalizations occur. Cost control shifts from reacting to overruns to managing the drivers of spend through daily operational levers.

This alignment also sharpens accountability. Leaders can see how small delays ripple outward. A missed behavioral health follow-up today becomes a readmission risk tomorrow. A stalled referral this week turns into a cost spike next month. When these connections are visible, accountability stops being abstract and becomes actionable.

In high-performing CCOs, technology ties clinical activity, quality performance, and financial outcomes into a single operating view. Leaders are no longer managing contracts through quarterly reviews. They are managing performance continuously, with clear line of sight from coordination to cost and quality.

At this point, technology is no longer just supporting value-based care. It is enforcing it. And that distinction explains why some CCOs consistently outperform others, even under similar regulatory and financial pressure.

What high-performing CCOs do differently with technology?

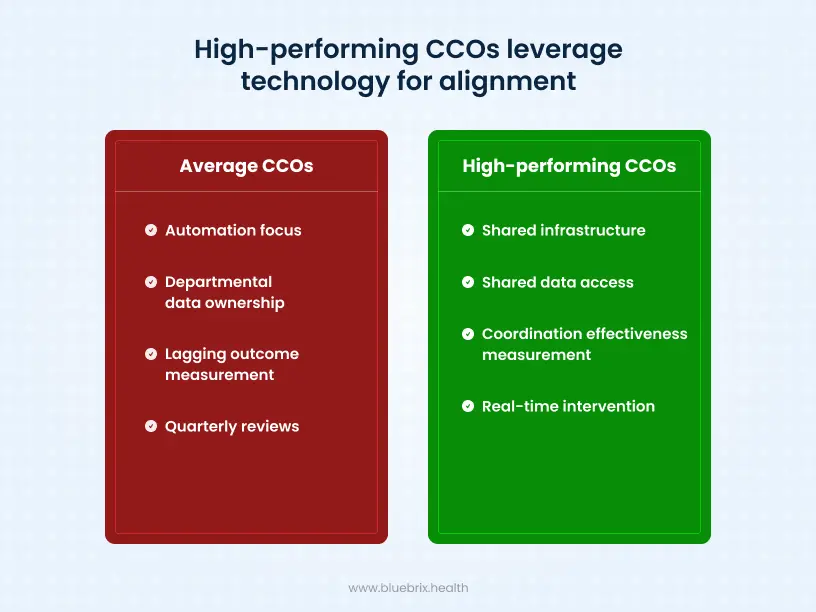

By this stage, the difference between average and high-performing CCOs becomes clear. It is not about who has more tools. It is about how technology is used to shape behavior, decisions, and accountability across the organization.

Average CCOs tend to focus on automation. They digitize referrals, streamline authorizations, and build dashboards that summarize activity. These steps improve efficiency, but they rarely change how coordination actually works. Processes move faster, yet the same gaps persist because the underlying operating model stays the same.

High-performing CCOs take a different approach. They treat technology as shared infrastructure rather than departmental software. Clinical teams, care managers, behavioral health providers, and community partners all work from the same operational view. Data is not owned by a function. It is shared across the organization, enabling coordinated action instead of isolated optimization.

Another key difference is what gets measured. Underperforming organizations focus on lagging outcomes such as readmission rates or emergency department utilization. High performers manage coordination effectiveness itself. They track how quickly referrals close, how consistently follow-ups occur within required windows, and how smoothly transitions move across settings. They understand that outcomes improve when coordination works, not the other way around.

Decision-making also looks different. Instead of relying on quarterly reviews or post-hoc explanations, leaders in high-performing CCOs intervene early. When workflows begin to drift or risk rises in a specific population, they adjust staffing, outreach, or processes in real time. Technology compresses the gap between signal and action.

In these organizations, technology is no longer something teams work around. It becomes the organizing layer that aligns people, data, and decisions. That alignment is what allows high-performing CCOs to deliver consistent results under value-based contracts, even as regulatory pressure and complexity increase.

With this contrast in mind, the final question becomes simple. What ultimately separates CCOs that scale from those that stall?

Execution is what ultimately defines the CCO model

At its core, the success of a Coordinated Care Organization does not hinge on vision or policy. Most CCOs already understand what integrated, value-based care should look like. The real differentiator is whether that vision can be executed consistently across daily operations.

When coordination depends on manual effort, delayed data, or individual heroics, performance becomes fragile. Gaps reappear under pressure, leaders manage in hindsight, and frontline teams carry the weight of systemic inefficiencies. No amount of clinical intent can compensate for an operating model that was not designed to scale.

High-performing CCOs make a different choice. They treat technology as the foundation of execution, not an accessory to reporting. Unified data becomes operational visibility. Visibility becomes owned workflows. Workflows feed decision intelligence. And decision intelligence connects directly to quality outcomes and financial accountability.

This is how coordination becomes reliable rather than reactive. It is how value-based care moves from aspiration to everyday practice. And it is how CCOs maintain control in an environment defined by downside risk, behavioral health integration, and increasing regulatory scrutiny.

The organizations that succeed are not doing more work. They are running better systems.